Now that the big investors have virtually stopped buying homes, a legislator wants to find a way to regulate them.

Typically the term “institutional investor” refers to private investment firms that buy dozens of residential properties with the explicit aim of generating a steady income stream through rentals. Often they invest the money of wealthy individuals and public pension funds, like those established for California state workers and teachers.

The best example is Blackstone, a publicly traded Wall Street firm that barrelled into the country’s single-family home market in the depths of the Great Recession in the late 2000s. Through its residential investment-focused subsidiary, Invitation Homes, Blackstone is now the largest owner of single-family homes nationwide. In California, they own about 13,000 homes.

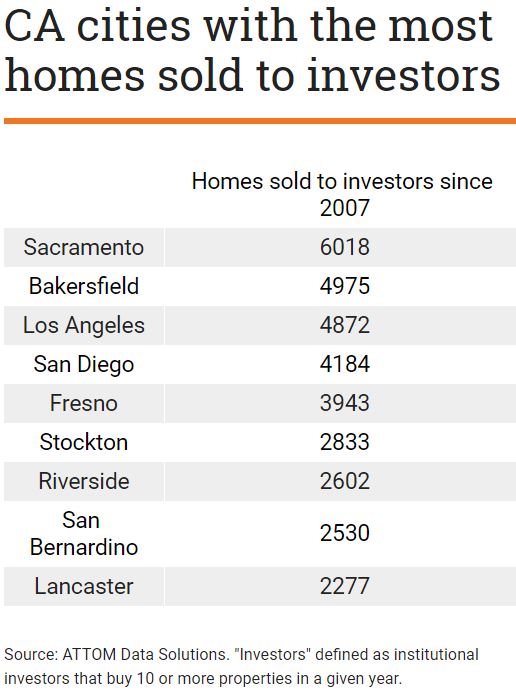

But firms such as Blackstone have stopped buying wide swaths of California homes. According to the real estate data firm ATTOM Data Solutions, which defines institutional investors as entities that buy 10 or more homes in a given year, institutional investors accounted for less than 2 percent of the state’s single-family home and condo sales in 2017.

That’s a pretty steep drop from as recently as 2012, when institutional investors accounted for about 7 percent of sales.

Why the decline? California no longer has a glut of cheap houses that can be easily gobbled up in foreclosure auctions. A sustained economic recovery and a lack of construction of new housing has sent housing prices skyrocketing. It’s now too expensive for institutional investors to buy lots of California homes. Blackstone’s Invitation Homes bought only 82 California houses last year.

“The low inventory and homeownership rates are good (for investors) if they own the property—it means more renters,” says Daren Blomquist, senior vice president at the real estate data firm ATTOM. “But it’s bad if they’re trying to acquire more properties.”

Reports of institutional investors making all-cash offers on California homes caught the attention of state Sen. Ian Calderon, Democrat from Whittier, when he was attempting to move out of his apartment and purchase his first house last year. While the 32-year-old lawmaker acknowledges that institutional investors don’t own a large chunk of California’s housing stock, he says he’s concerned their influence is yet another hurdle for young homebuyers to overcome.

“I just want to be able to have more information about these firms, and ultimately I want to advantage first-time homebuyers,” said Calderon. “I want to make sure that people aren’t getting screwed.”

Multiple attempts by Calderon to impose more transparency on institutional investor activity while blunting their ability to make all-cash offers have not gone far in the Legislature. Two years ago, a bill that would have forced homeowners to wait 90 days before selling to large institutional investors failed to clear both chambers with that provision intact.

Last year, a bill that would have required investors who own more than 100 properties in California to register with the state and provide detailed information on their activities again failed to reach the governor’s desk. Caldeorn says there’s a good chance that bill will be resuscitated this year.

The California Apartment Association, which represents landlords across the state for both multifamily and single-family units, has opposed much of Calderon’s legislation, arguing that much of the information it seeks is available in public stock exchange filings. That’s mostly true, but that only applies to publicly traded firms, and the data is not in the most accessible format.

Landlords also says Calderon’s bill doesn’t address the root cause of the problem.

“The bottom line here is about supply,” said Debra Carlton, lobbyist for the California Apartment Association. “There’s just not enough housing to go around so you end up in these unfortunate situations where people can’t buy and can’t afford a place to rent.”

Link to Article

Why the decline? California no longer has a glut of cheap houses that can be easily gobbled up in foreclosure auctions.

Pretty sure Blackheart got most of their properties in bank bundles without any foreclosure auction.

In one particularly egregious example Duetsche Bank sold a large portfolio to Blackheart at the same time they extended a several billion dollar line of credit to… wait for it… Blackheart. Nonperforming mortgages magically disappear from the bank books and at the same time their commercial lending increases for the win-win.

As an asset manager for Fannie Mae properties back in 2008 thru 2013 I can confirm that approximately 25% of my entire REO inventory was purchased by institutional investors. Some states were close to 100%. And Blackstone was the largest of these buyer types. I don’t think the housing market would be in it’s current low inventory conditions if they hadn’t taken advantage of the market at that time. They need to be incentivized to liquidate those residential holdings by our government.

They need to be incentivized to liquidate those residential holdings by our government.

Let’s incentivize everyone by reducing or suspending the capital-gains tax for a year or two. It’s the #1 reason people hang on to their rentals forever.

Good to hear from you, Wes!