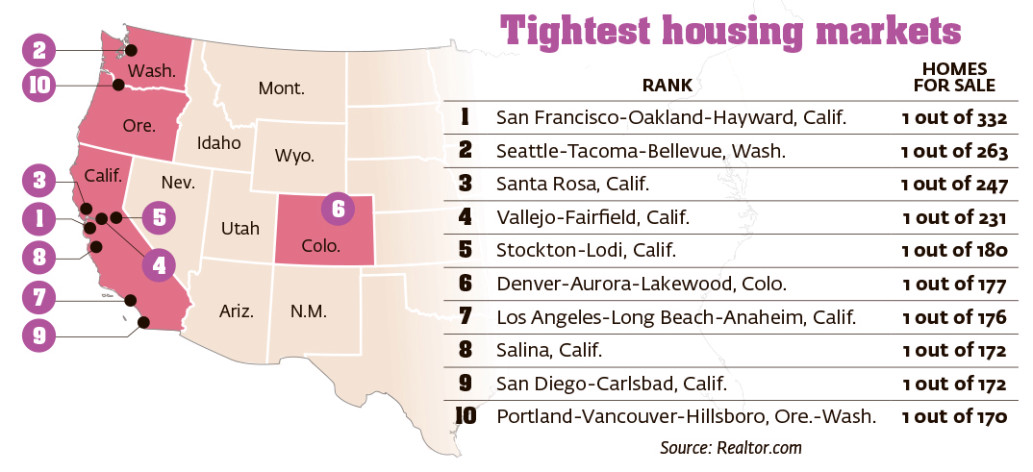

Wondering why you can drive for blocks and not see a for-sale sign?

1 out of 172!

http://nypost.com/2017/09/02/are-we-headed-for-another-housing-collapse/

An excerpt:

NAR’s Fears points to a number of trends: First, homeowners are staying in place longer, limiting the number of existing homes for sale. Low unemployment rates are keeping them from leaving town in search of work. High home prices are inspiring them to remodel rather than relocate within their communities, if they want a different kind of house. First-time buyers who can afford it might buy a home that can accommodate two kids instead of one, precluding a move a couple years after their purchase. Grandparents are staying put to live near their kids, rather than fly off to retirement far away.

Second, new construction is still springing back from the 2008 recession. Home builders have had a hard time keeping up with population growth since then, in most cities. “There was a high cost for dealing with regulation, a high lumber tax on Canadian framing lumber, a decline in the labor pool,” says Fears. But the construction industry has shown signs of life. In July, according to US Census Bureau and Department of Housing and Urban Development data, housing completions were 8.2 percent higher than they were one year ago, though 6.2 percent lower than they were in June.

Even when they do build, developers are restricted by urban planning and geography, in certain states more than others. In Portland, Ore., cities are required by state law to form an urban growth boundary around its perimeter, controlling expansion onto farm and forest lands.

“Since about 2009, a lot of areas inside the boundary have been dormant,” says Victor Bulbes, broker with Keller Williams. “Builders have been reluctant to get back in the game.”

The Portland metro area, like other Western cities, is popular, with a record low 4 percent unemployment rate and stable population growth. Since 2010, the city has grown 8.3 percent, according to US Census data.

Lifestyle preference also drives the market.

In Denver, where the number of available houses has plummeted in the last seven years from 12,000 to 2,000 and median prices grow by around 9 percent annually, most people want to live in the urban core, says David Schlichter, Denver-based broker with Keller Williams’ The Schlichter Team.

“There is definitely plenty of land here, at the base of the mountains, next to the foothills. There is some development in the outskirts, but where people want to be, in the city, there is only finite space.”

From 2012 to 2015, with the exception of 2014, Denver experienced double digit price appreciation.

“It will taper off,” says Schlichter. “You can’t have that in perpetuity because at some point, another city becomes more attractive. Now, there are way more people moving here than leaving. Each week, I get a call from someone from the Bay Area who is fed up. Here, houses are half the price. To them, this is paradise.”

Still, lingering fears from the past housing bubble and a present-day crisis in London, where astronomical prices mean young buyers are entirely locked out of the property ladder, are stoking concerns that market growth in the US could one day become unsustainable.

In March, William Poole, a senior fellow at the Cato Institute, wrote a column for cnn.com, pointing to concerns about the country’s two biggest mortgage lenders, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. “In Freddie’s 2016 Annual Report, the agency says 36 percent of its obligations are ‘credit enhanced,’ meaning they carry mortgage insurance of one sort or another, which is typically used for weaker mortgages,” Poole wrote. “If these weak subprime mortgages begin to fail in large numbers, so also will the insuring companies.”

Jonathan Miller, a real-estate analyst at Miller Samuel, is unmoved by such arguments. He says the average buyer today has an average credit score “well above 700. They are some of the highest average credit scores in history.” He added that any subprime failures would be offset by the quality of most American borrowers being “unusually high.”

For now, Schlichter in Seattle agrees. “Barring some calamitous event, I don’t feel that our local economy is threatened to the point that a bubble is about to burst,” he says, then added: “But we have a highly unpredictable president, and everything could change with a tweet.”

NSDCC Total Detached-Home Listings, Jan – Aug, and Median LP:

2012: 3,335, $975,000

2013: 3,685, $1,150,000

2014: 3,566, $1,250,000

2015: 3,797, $1,290,000

2016: 3,920, $1,399,000

2017: 3,512, $1,425,000

Could there be fewer listings next year?

I have been staring at the same 2-3 houses in my neighborhood that have remained unsold for quite some time.

this story needs more context.

“I have been staring at the same 2-3 houses in my neighborhood that have remained unsold for quite some time.

this story needs more context.”

Do the homes you cited have zillow pages?

You can’t properly criticize the local dating scene if you’re keying off a couple of mean old cat ladies.