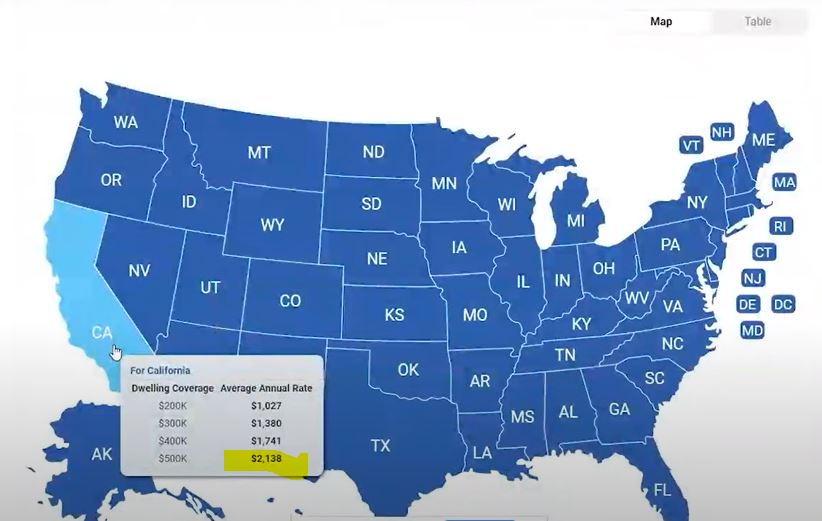

Currently buyers are having to pay 2x or 3x the previous bill for homeowners insurance, due to the lack of options because the big insurance companies have stopped writing policies in California. Some are blaming climate change, and guys like Carl Demaio are blaming Biden, but with a little digging it looks like the insurance-companies requests to raise premiums have been stalled for years. California’s average home insurance rate is $1,225 per year for $250,000 in dwelling coverage is about 14% lower than the US average, according to Bankrate. The thought of insurance premiums being 30% higher sure sounds better than 2x or 3x!

Full story from the LAT:

After a summer that saw many of California’s top home insurers pull back from the state market, Insurance Commissioner Ricardo Lara announced Thursday that he struck a deal with the insurance industry to encourage new coverage in the state.

Insurers, Lara said, agreed to return to the high-risk fire zones in the state in exchange for a number of concessions that will make it easier, in theory, for them to get higher rate increases through the state regulator more quickly. The announcement comes the week after negotiations in Sacramento over a legislative response to the home insurance market fell apart.

Gov. Gavin Newsom also issued an executive order on Thursday afternoon commanding the insurance commissioner to “take prompt regulatory action to strengthen and stabilize California’s marketplace” and consider whether emergency action could be necessary.

The changes are slated to go into effect by the end of 2024, but the hope is that insurers will return to writing new homeowners policies in California sooner. Leading insurers such as State Farm, USAA and Allstate all have requests for rate increases pending with the state insurance department, and are requesting hikes of 28.1 percent, 30.6 percent and 39.6 percent, respectively.

If approved, each company would be allowed to raise its total premiums in the state by that amount, but the rate increase can be distributed differently among homeowners: a cabin in the woods might see a 200 percent jump while a home in San Francisco could see little to no change.

Since the massive fire years of 2017 and 2018, home insurers have been gradually withdrawing from the most fire-prone parts of the state. As a last resort, homeowners and businesses in those areas have turned to California’s FAIR plan, a backstop insurance provider funded by the companies that do business in the state, which charges much higher rates to provide less coverage in high-risk areas. The result of this pullback can be seen in the numbers: the number of FAIR plan customers more than doubled since 2018, up to 3 percent of the total state market.

Under this new deal, insurers have agreed to return to those fire risk zones up to a certain threshold equivalent to 85 percent of their statewide market share. That means State Farm’s California home insurance branch, which covers more than 21 percent of the state market, would be required to cover 18 percent of the houses in fire zones. The net effect will be that major insurers will combine to cover 85 percent of customers in those areas, with the FAIR plan and other higher-cost insurers picking up the remaining 15 percent.

In exchange, Lara has offered to loosen certain elements of insurance regulation in California. Under the existing system, insurers need to apply to the Department of Insurance to raise their average rates across the state, and provide reams of supporting documents to justify the price hike. The process also allows for consumer advocates to intervene along the way to serve as watchdogs in the process.

This system was born in 1988, when California voters approved Proposition 103, and the first elected commissioner on the job, current Rep. John Garamendi, D-Walnut Grove, put a regulatory regimen in place above and beyond the text of the ballot measure. Those rules meant that insurance companies were not allowed to pass along the cost of reinsurance — insurance policies that insurance companies buy to cover their big losses — to policyholders, and that they could use only historical loss data, rather than forward-looking simulations, to request permission for a price hike.

Insurance industry representatives have been clamoring for both of those rules to be abolished for years, with the calls intensifying this summer as major insurers hit pause on writing new business in the state, citing rising reinsurance and catastrophic loss costs — though they said the spiking cost of materials and labor for home repair and rebuilding also played a major part in their financial strain.

Now, Lara said, he plans to go ahead and allow insurers to use catastrophe modeling that takes into account the projected impacts of climate change and other shifting factors when asking to raise rates. He also said that insurers will be allowed to include reinsurance costs for California coverage into rate filings, though the announcement did not go into specifics. Companies will be allowed to use these models only if they comply with their commitment to increase coverage in the state and reduce the FAIR plan population.

Lara also said that the insurance department finalized a change to the FAIR plan, first announced months ago, which increases the dollar amount that the plan is allowed to cover for commercial properties. Before, it was capped at $7.2 million to $8.4 million for different types of commercial properties, which include condo associations, homeowners associations, affordable housing developments, and businesses such as wineries that are often located in areas with high fire risk. Now, that cap has been raised to $20 million for all types of commercial properties.

Lara also said he aims to speed up the overall process by accelerating the pace of rate approvals, and that the new state budget includes funds for hiring more staff to process filings. He will also require that intervenor filings be made public, which Lara argues will increase transparency and make it easier for more consumer advocates to participate.

The consumer advocates in question fundamentally disagree with Lara’s approach.

Consumer Watchdog, the consumer advocacy group that serves as intervenor in the majority of rate filing cases, wrote a letter to Newsom earlier Thursday urging him against declaring a state of emergency to give Lara the power to change the regulations with a lower degree of public comment.

“Insurance Commissioner Lara should not be trusted with these extraordinary powers,” the group wrote, noting that he has refused to meet with consumer advocates, spent the summer in conversation with industry lobbyists, and is under investigation for campaign finance law violations by the California Fair Political Practices Commission.

Harvey Rosenfield, the author of Prop 103 and founder of Consumer Watchdog, and other consumer advocates have long held that forward-looking catastrophe models amount to a black box that insurers can use to manipulate rate requests without showing their math.

At past hearings, participants have raised the idea of creating a shared, transparent state-administered model, or imposing auditing and transparency requirements on the companies developing the models. But modeling companies have argued that too much transparency would amount to a violation of their competitive edge and trade secrets. It is unclear how Lara plans to thread this needle.

The same criticism holds for reinsurance costs, which are subject to an unregulated global market — allowing companies to pass them through would amount to a loophole in California’s strong price control system, according to consumer advocates.

Dean writes for the Los Angeles Times.

Link to Article

Shakedown and corruption. They weren’t losing money at the old rates. At least the big city Democrat donors were protected.

On a side note, let’s hope that the rapid runup in home prices doesn’t get thrown into the equation. Nobody insures the land – premiums are purely based on the cost of replacing the sticks and stucco, and that should be all that matters when calculating the premiums.

Carl made a big stink about the cost of lumber sky-rocketing, and in early 2021 the cost of a thousand board feet was up around $1,600. But now it’s down to $502.00 per. Wouldn’t it be effective policy to have the insurance premiums reflect the actual changes every year? Or every month?

Careful with that math. If the Dawghaus were to burn it is entirely possible that it would be worth the same empty based upon recent sales of comps and nearby empty lots.

A brand-new Dawghaus would surely be worth more than the existing?

I think that’s why arson is such a lucrative option.

Only because I cannot figure out how to start an earthquake or flood.

Thing is, a replacement Dawghaus would be a poor use when the houses to either side are twice as large and twice the price.

Rising insurance costs based on actual risk should be one of the factors that people have to take into consideration when they decide whether to build, buy and live in homes deep in forests, on beaches or on top of earthquake faults. Regulations that artificially reduce actual risk are as bad an idea as allowing rate increases based on models nobody knows the basis of because they’re “trade secrets.”

If risk modeling is to be used, the state should create its own and require all insurers to use it. Alternatively, the state could accept proposals from modeling companies to have their model declared the “official state model,” and trade transparency and the potential exposure of their “competitive advantage” for the elimination of competition and being the only model CA insurers are allowed to use.

As for passing reinsurance costs to the consumer, not only no but hell no. Reinsurance is something insurance companies do for their benefit. The consumer gets nothing out of it. If anything, insurance companies that are not sufficiently capitalized to cover their own risks without reinsurance probably shouldn’t be allowed to sell policies at all.

If anything, insurance companies that are not sufficiently capitalized to cover their own risks without reinsurance probably shouldn’t be allowed to sell policies at all.

Good point GeneK! An interesting crossroads between government and private enterprise.