Here is a bunch of happy talk by three ivory-tower guys, but they never considered the consequences. Preventing foreclosures and pushing down mortgage rates helped to create a safety net that caused buyers to rush back into the market. Prices went up too quickly, trapping homeowners into their existing homes, rather than being able to move up, down, and around. Now only the affluent can afford a house, rents are skyrocketing, and homelessness is running rampant.

Hat tip to daytrip for sending this in:

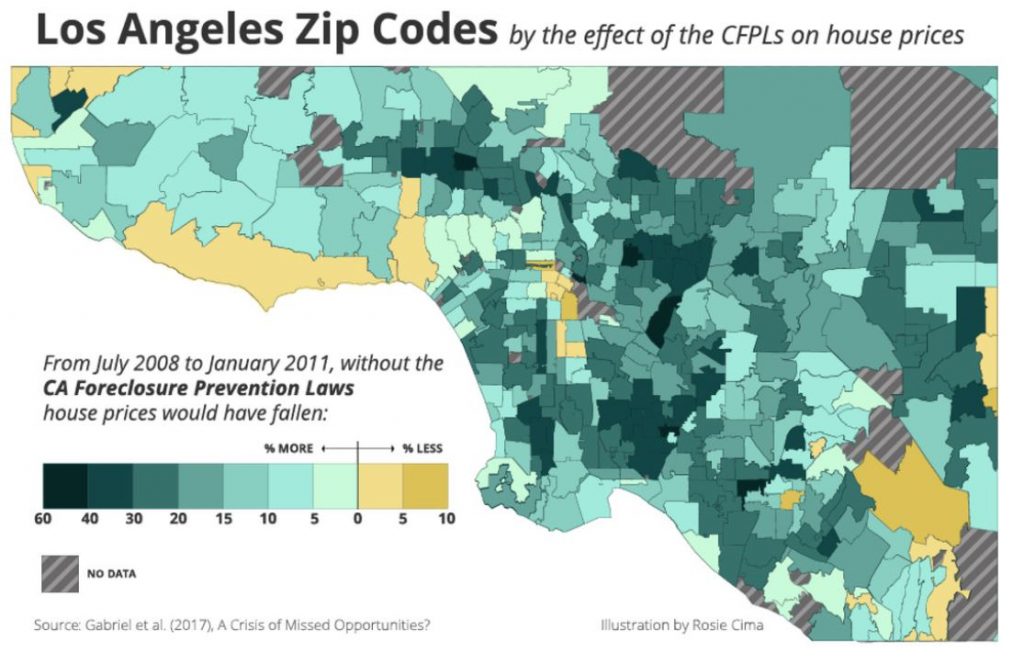

The subprime mortgage crisis that broke out a decade ago is widely recalled as an uncontrolled and destructive plunge in housing prices. New research suggests, however, that at least one effort to halt the plunge was in fact quite effective. UCLA Anderson’s Stuart Gabriel, the Federal Reserve Board’s Matteo Iacoviello and Copenhagen Business School’s Chandler Lutz found that California’s 2008 anti-foreclosure law prevented the loss of some $470 billion in home value wealth.

The California law, examined against other anti-foreclosure efforts, stands as a potential model for future housing crisis interventions. The researchers found that the passage and implementation of the California Foreclosure Prevention Laws (CFPLs) simply and effectively made foreclosures more difficult and more expensive for lenders to initiate, slowing what could have been a more calamitous spiral in housing prices.

Limiting foreclosures is key to containing a housing panic. If foreclosures go unchecked in a crisis, they can spread. Because foreclosed-on houses are “priced to sell,” the first wave of foreclosures depresses the prices of all homes in the area. Additional borrowers who can’t make their payments then cannot sell without taking a loss, causing a second wave of foreclosures, further depressing prices. And a downward spiral has begun.

A wave of foreclosures seems to also produce a “disamenity effect”: someone who defaults on her mortgage slacks on maintaining the house, and its appearance of disrepair drags down the desirability of the neighborhood.

In some states, the law requires that lenders process foreclosures in state courts. Judicial foreclosure laws result in foreclosures costing much more time and money than they do in states like California, which does not have judicial foreclosure laws. The upside to not having judicial foreclosure laws is efficiency — for both the lenders and the government.

The downside is that, following market shocks, foreclosures are in danger of spiraling out of control, as they seemed to be in California in 2008. In the midst of the crisis, hundreds of thousands of people lost their homes to foreclosure, and it emerged that banks were “robo signing” on the procedural documents: They were pushing foreclosures through at an unreasonable rate, often without justification or authority to do so.

In 2008, California state senator Don Perata of Oakland authored SB-1137, the first of the California Foreclosure Prevention Laws. SB-1137, and the 2009 California Foreclosure Prevention Act after it, both increased the time and the monetary cost of foreclosing on property in California.

“The mortgage crisis is taking a terrible toll on Oakland and the rest of California,” said Perata, as quoted in the SB-1137 analysis. “It is crucial that we give homeowners the tools they need to avoid foreclosure when possible because that’s the best outcome for everybody.” Gabriel, Lutz and Iacoviello’s research suggests these laws saved the state hundreds of billions of dollars.

Link to ArticleHere’s a glimpse of how it’s working on the street today:

Thanks for sharing. What neighborhood is that?

The Bay Collection.

I’d argue that limiting foreclosures led to a moral hazard that virtually guarantees a future crisis worse than the last one.

Why will there by another crisis if the economy is so great? I’m in Los Angeles. Everyone’s still buying! They have huge down payments. I see a slow down but a crash?