Freddie Mac’ research finds that today’s seniors (persons born after 1931) are staying in their homes longer, and aging in place. While Millennials have historically low rates of homeownership, the rates among seniors are high relative to previous generations.

The company estimates that this trend accounts for about 1.6 million homes that have not been available for sale. This represents about one year’s typical supply of new construction and about half the 2.5 million units need to meet demand. This gap will increase the relative price of owning versus renting, making renting more attractive to younger generations but it also puts upward pressure on both house prices and rental rates.

The why of this trend can be explained by a few key factors; better health and higher levels of education. The economists say this pattern is likely to increase over time as improvements in health care and technology make aging in place easier. They cite as an example the ability to Skype with a doctor.

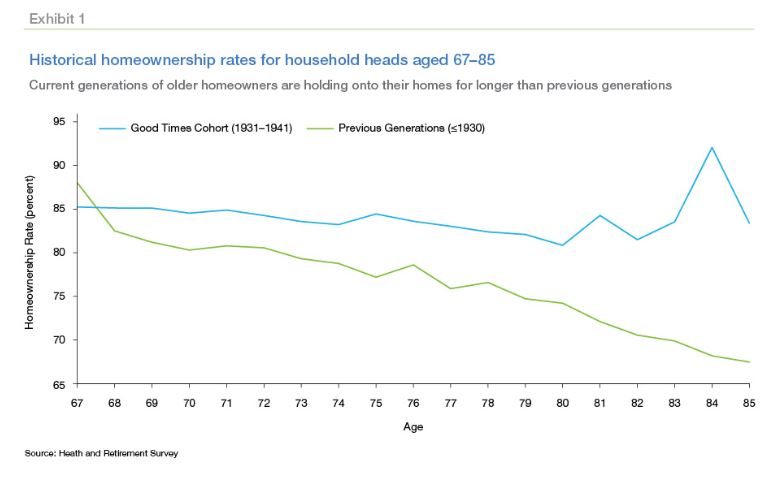

The research compared homeownership rates for seniors aged 67 to 85 in two different periods. The current crop of seniors, they call them the “Good Times” cohort, were born in some bad times between 1931 and 1941 but with the benefit of relatively good times through their lifetime. The “previous generations” combines the generation born before 1924 and the “children of the Depression” born between 1924 and 1930.

The aging in place trend becomes apparent right after members of the two cohorts reach 67. Between that age and 87 the homeownership rates dropped by 11.6 percent for previous generations but only 3.6 percent for the Good Times cohort.

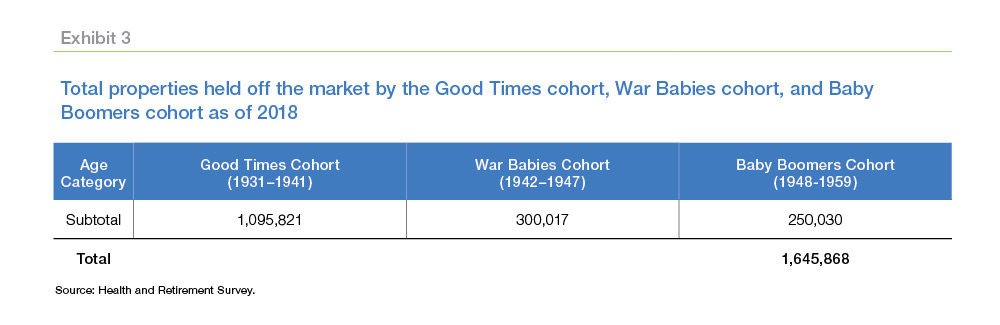

To reach their estimate of how many housing units have been held off the market by recent cohorts of senior citizens, the economists engaged in a thought experiment and evaluated a “counterfactual.” What would have happened if the Good Times cohort had behaved like prior generations? Since the diversion between the two cohorts begins at age 67.4, they used the pattern of the previous generations to develop a scenario to answer that question.

These estimates suggest that had the Good Times cohort transitioned as previous generations did, there would have been around 1.1 million more housing units available by 2018.

Generations that came along after the Good Times cohort, the “War Babies” (1942-1947) and “Baby Boomers” (1948-1959) are also expected to stay in their homes at higher rates, and thus contribute even more to the number of houses held off the market. Similar calculations for those two groups lead to an estimate that an additional 550,000 homes were held off the market by these cohorts by 2018, as shown in Exhibit 3. The combined total of 1.6 million units is 2.1 percent of total owner-occupied housing units in the United States as of 2018.

I’m a 1955 vintage. Good time to sell?