Those with less skin in the game are typically the people who have the most trouble in a down market. Apparently, the potential profit must be so large that the investors overlook that – or figure there is little chance the government will let the market go down again?

Several years after her divorce, Tricia DeWaal was still living in the 3,200-square-foot home where she’d raised her children. When her youngest moved out, DeWaal knew it was time to downsize.

“For what I wanted, I had a 20% down payment, but that would pretty much clean me out in terms of cash,” DeWaal told MarketWatch. “I wanted to have some backup.”

After lots of online research, DeWaal came across a company called Unison, which had an intriguing sales pitch. The company’s home-buyer program offers buyers money for a down payment in exchange for a share of equity in the home, to be paid back when the owner sells.

DeWaal had what she called a “very positive experience.” “It’s definitely a good thing for somebody who’s trying to afford a certain amount that they can’t quite get to,” she said.

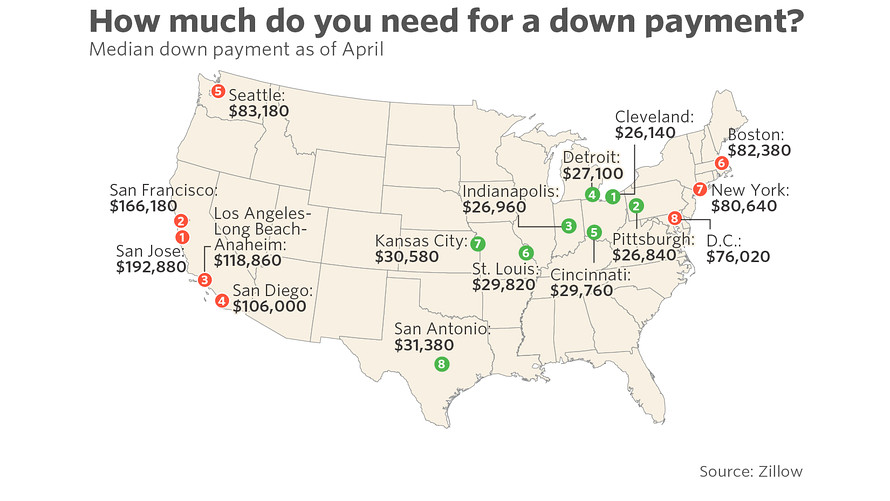

Homeownership’s biggest barrier to entry, the down payment, looms larger and larger all across the country. Student debt payments and high rents are formidable barriers to saving, and, while there are plenty of ways to buy a home with less than 20% down, all require some form of mortgage insurance, making them more expensive.

For a long time, nonprofits have tried to help home buyers up and over the hurdle. But in today’s tight market and constrained lending environment, fintech companies are seeing an opportunity as well, particularly in the hottest housing markets, where 20% down can mean six figures.

Unison and a competitor, OWN Home Finance, which is set to launch a similar product later this year, got started years ago with a slightly different business model: allowing homeowners with high levels of accrued equity a means of tapping into that money.

Here’s how Unison’s model works: The company contributes up to 50% of the down payment, or 10% of the total cost of the home, and, then, when the owner sells, Unison takes a share of the profit, usually 35% — or a share of the loss, also usually 35%.

For many housing market observers, the idea makes a lot of sense.

“I love to see the experiment,” Brett Theodos, a senior research associate at the Urban Institute, told MarketWatch. “It’s really intriguing as home prices appreciate and incomes don’t. It feels like a missing rung in the ladder between renting and owning. We have so many investment vehicles that you can get into for small amounts of money, but homeownership is very much an all-or-nothing proposition.”

Still, with programs like these, according to Theodos and other experts, the devil is in the details.

Because the companies make money only when a home is sold, assumptions about lofty price gains must be met. (It’s also possible to buy out the equity stake before selling, according to the terms of the agreement between the company and the borrower.) Unison notes that “special provisions” will apply if homeowners sell in less than three years because “in order for home prices to change, time must pass.”

There are additional considerations that may apply to a mortgage on a home with an equity stake that aren’t an issue for most homeowners. For example, Unison says it will need to review — and charge a fee for — any documents used in a future refinancing. And, for now, borrowers interested in an equity-sharing scheme must use a partner lender approved by Unison or OWN.

It’s also difficult to know how the shared equity relationship will withstand the normal milestones that make homeownership challenging enough with just one owner. Unison notes that if a property has not been “properly maintained” at the time of sale, it may use a third-party appraiser or inspector to assess how much of the lost value is due to improper upkeep in order to allocate that lost appreciation to the homeowner, not the company.

(The home-buyer program hasn’t been around long enough for any customers to have sold a house that was purchased with shared equity, though customers of an earlier pilot program have both sold and bought out Unison’s stake, steps that the company says went very smoothly.)

Both Unison and OWN Home Finance say they get their funding from pension funds and endowments — the types of investors normally accustomed to holding “patient equity” stakes.

When OWN launches, Bailey said, it plans to target low- to moderate-income buyers with median incomes of about $55,000 to $60,000, attempting to buy homes priced at about $400,000 to $500,000. The company has registered as a “public benefit corporation,” a for-profit entity with a social mission.

The lean profit margins and barriers to scale leave some observers, like Theodos, unsure how attractive these models are to investors. “It seems clear to me that it could benefit consumers if you can get the right mix of the payback and equity sharing. I’m not sure that you can. I don’t know if it’s workable in terms of what investors need for repayment.”

Unison has partnered with Freddie Mac to test out automating the process of underwriting mortgages with an equity stake. Freddie Mac declined to comment for this story.

Sounds like a scam to leave the homeowner out to dry if they ever sell their home. So if a home cost 500k, the owner puts down 50k and Unison puts down 50k. Lets just say in 10 yrs the home is the same price due to umemployment and interest rates. Assuming 9% of the sale prices goes to commissions and fees when selling the home plus 35% stake to Unison, Unison gets 175k (not bad) in the pocket and the owner is left with 280k when the loan balance still exceeds 310k. The owner will walk away paying 30k back to the bank and left with $0 for another home. PMI or not buying something you can’t afford would be the better option.

Agreed – I’d rather pay PMI than have a 50/50 corporate partner.

Sounds like a “reverse mortgage lite.”

“You say you’d like to do a reverse mortgage, but dread the steely stares, and passive-aggressive remarks during Thanksgiving dinners?

Try Reverse Mortgage Lite!

‘It Just Might Work Out!'”

35% of profit not 35% of sales price.

The benefit to them is owner covers carrying costs, property taxes, etc the whole time.